Chicago is home to one of the world’s finest collections of 20th Century public art and sculpture, however, a number of important sculptures have recently vanished. These sculptures are an important part of Chicago’s artistic and cultural heritage and their loss is profoundly embarrassing and a tragic blow to Chicago’s exceptional collection of public art. It damages Chicago’s reputation as an international architectural and cultural capital, which is so important for drawing millions of tourists and their billions of tourist dollars to Chicago every year.

The monumental Henry Moore bronze, called “Large Internal-External Upright Form” that once dominated the lobby of Three First National, vanished during a lobby remodel and then resurfaced in 2016 when it sold at auction in London for millions. In March 2017, Alexander Calder’s “The Universe” kinetic sculpture was carted off to storage prior to a lobby renovation and its future is pending the outcome of a lawsuit regarding ownership. This highly whimsical kinetic sculpture in lobby of the Sears Tower was unveiled on the same day, October 25, 1974 as “Flamingo” in Federal Center. The grand-scale of Harry Bertoia’s “Sonambient” sound sculpture on the plaza of the Standard Oil/Aon Building with its soaring brass rods was lost when the plaza was redesigned in 1994 and most of the sculpture hauled off to storage. Five pieces of the sculpture were sold at auction in 2013 and a new round of plaza alterations jeopardize the few elements of the sculpture that remain.

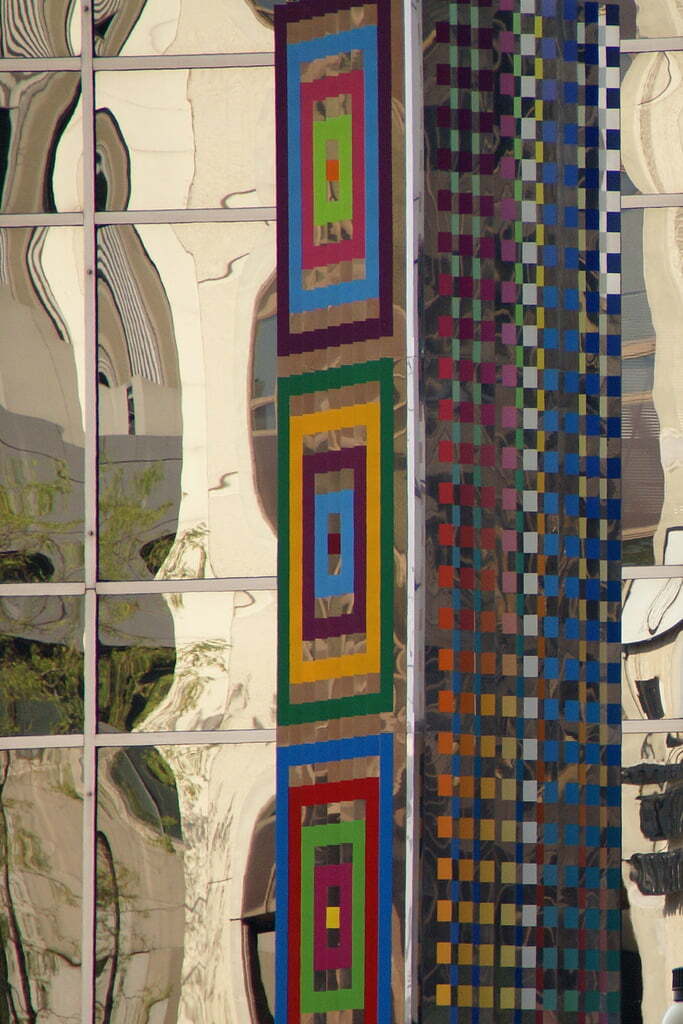

The Agam sculpture titled “Communication X9” was dedicated in 1983. This 43-foot tall sculpture by Israeli artist Yaacov Agam used colorful prismatic elements that appear to move as pedestrians walk past this bustling Michigan Avenue corner in front of the Stone Container/ Crain Communications Building at 150 N. Michigan Avenue. This iconic sculpture was removed in August 2018.

According to a statement from property management CBRE to Crain’s Chicago Business, “the building is undergoing a significant renovation project that will change the character of the building in a way that is no longer compatible with the sculpture. We are taking great care to properly remove and store the sculpture with the hope that it can one day be enjoyed again in a setting that is in keeping with the spirit of the piece. While ownership may sell the piece, they also are entertaining the idea of donating it if they are able to identify an appropriate recipient.”

Like so many other monumental works of Chicago art, this sculpture will likely end up sold at auction.

There are other important Chicago sculptures in danger. There is concern regarding the future of the Marc Chagall’s “Four Seasons” mosaic at First National Bank/Chase Plaza, as credible sources report that Chase Plaza has been quietly marketed for sale as a buildable site with potential for a new high-rise development. Originally, intended to be viewed from the tall buildings surrounding the Plaza, the mosaic sunburst and rainbow stripes that once covered the top surface of Chagall’s masterpiece have already been lost.

Jean Dubuffet’s fiberglass sculpture “Monument with Standing Beast” has been located in the plaza in front of Helmut Jahn’s Thompson Center at 100 W. Randolph since 1984. While it reflects on the open space of the Thompson Center’s architecture, it is comprised of four massive forms which invite viewers to enter and walk through the sculpture. Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner has frequently called for the state-owned property to be sold for a super-tall new development which would endanger the future of the sculpture.

Other notable Chicago sculptures that should be protected include Claes Oldenburg’s “Batcolumn”, Joan “Miro’s Moon, Sun, and One Star”, and Alexander Calder’s “Flamingo”. Chicago was one of the first and largest municipalities to require the inclusion of public art into its public building program. While Chicago was exemplary in providing its citizens with inspirational architecture and public art, it never developed criteria for protecting these public works of art. In fact, “The Picasso” is the exception and is one of the few pieces of public art that is protected from being removed or altered in anyway as part of the Richard J. Daley Center and Plaza Chicago Landmark Designation.

Mayor Emanuel and Choose Chicago, the city’s official tourism wing, dubbed 2017 the “Year of Public Art in Chicago” to celebrate Chicago’s magnificent art collection in the Loop and artistry throughout the neighborhoods. Ironically, it proved to be the year in which some of Chicago’s greatest public art disappeared from the city.

The possibility of losing such extraordinary masterpieces is truly shocking. Preservation Chicago is profoundly concerned about this trend and is advocating for a Thematic Chicago Landmark District to be created to protect the most important examples of 20th Century Chicago Public Art, along with the contextual plazas in which they are installed.

Preservation Chicago believes that important Chicago sculptures should remain in Chicago in the public view. If they cannot remain at their historic location, then they should be donated to major Chicago art institutions such as The Art Institute of Chicago or The Museum of Contemporary Art. To this end, Preservation Chicago has been in touch with senior leadership at The Art Institute of Chicago who have indicated an openness to the donation of important world-class works of art.

Additional Reading