St. Martin’s Church / St. Martin de Porres / Evangelical Chicago Embassy Church

Address: 5848 S. Princeton Avenue

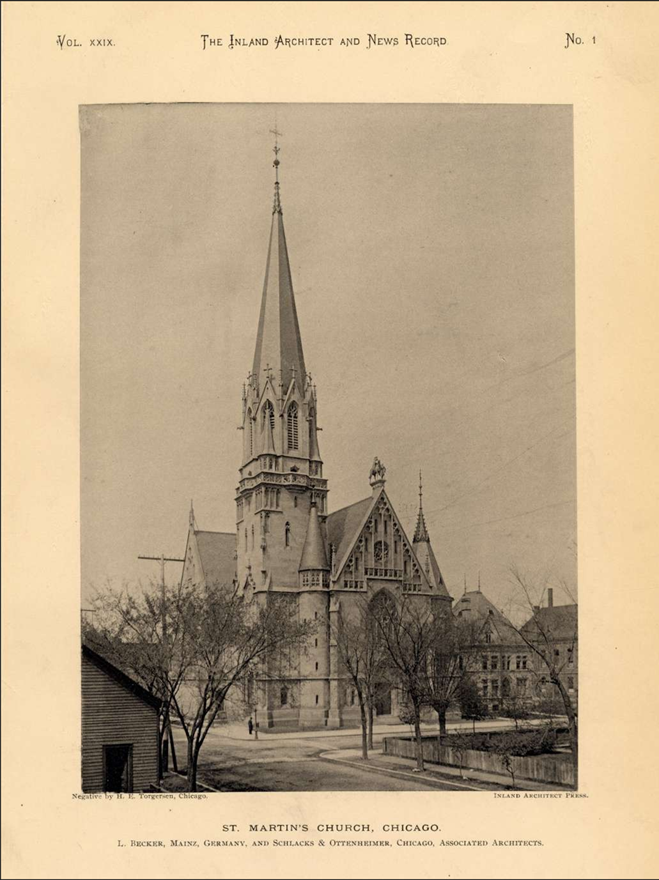

Architect: Henry J. Schlacks; Louis Becker

Date: 1895

Style: Gothic Revival

Neighborhood: Englewood

OVERVIEW

Historic churches are some of both the oldest and finest examples of architecture throughout Chicago’s neighborhoods. They are part of the fabric of the city and beloved landmarks that provide a direct connection to a neighborhood’s past. The prominent ecclesiastical building at the corner of Princeton Avenue and 59th Street in Englewood, originally St. Martin De Tours Church, is an outstanding example of the city’s architectural legacy. St. Martin is reflective of a time when Chicago was famous for having churches on nearly every block, with one for nearly every ethnic group and immigrant community.

St. Martin De Tours was built in 1895 for Chicago’s growing German Roman Catholic community. The plans

for the building were drawn up by Louis Becker of Mainz, Germany, and executed by accomplished Chicago architect Henry J. Schlacks, widely regarded as one of the city’s finest ecclesiastical architects. Trained at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and in the offices of Adler & Sullivan, Schlacks specialized in the design and decoration of churches and later founded the Architecture Department at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana. Per an 1894 article published in Inter Ocean Newspaper, St. Martin’s design was described as a “conscientious endeavor to put forth for the first time in Chicago, if not the country, an edifice of pure style in Gothic church architecture.” Today, St. Martin’s stands as a significant historical edifice or monument from the Gothic Revival movement in the United States and remains one of the finest examples of German Gothic architecture in the country.

St. Martin’s further also stands as a testament to Englewood’s demographic shift, and to the long tradition of church buildings being repurposed for a diverse set of congregations. The church was later renamed to St. Martin De Porres Catholic Church to honor the neighborhood’s large African American population, before its eventual closure in 1989 due to dwindling attendance. The building reopened in 1998 as the Evangelical Chicago Embassy Church, serving an Evangelical Black congregation.

St. Martin’s has been shuttered since 2017 and continues to suffer from years of deferred maintenance and considerable deterioration due to vacancy and neglect. St. Martin was previously listed as a Chicago 7 Most Endangered in 2022, but unfortunately conditions have remained largely unchanged. Preservation Chicago again urges the restoration of this magnificent and storied church, and its creative reuse could spark both spiritual and social renewal at this corner of Englewood.

HISTORY

St. St. Martin was initially organized for the German Catholic Community in what was then the suburban town of Englewood in 1886. Shortly thereafter, a combination church and school, designed by German-born architect Adolphus Druiding, was erected on Princeton Avenue and completed by Christmas of that year. The German- speaking population of Chicago had grown tremendously after 1872, and St. Martin was the third German church built in the Englewood area (the two earlier churches have since been demolished). The church was built up f ro m i ts hum b le beginnings through the enthusiasm of its first pastor, Rev. John Schaefer, and with the s u p p o r t o f h i s parishioners. As the congregation grew, a new rectory was built in 1894 at 5842 S. Princeton Avenue to replace the original parish residence, which was converted into a convent. That same year, the cornerstone for a new, permanent church was laid, marking the transition from the modest initial structure to the grand Gothic edifice completed in 1895. The construction cost approximately $150,000. Just a year after St. Martin De Tours was erected, it was called “the pride of the German residents of that part of the city,” and its members continued raising funds to furnish the building with four new bells, statues, and a grand organ. The crown jewel of the church was an 1895 statue of St. Martin and the Beggar, carved by noted sculptor Sebastian Buscher (1849- 1926) out of poplar and weighing 1,600 pounds. Prominently placed atop the building’s high gable, it was one of the first colossal wooden statues completed in the United States. The figure represents a 4th-century Roman soldier who famously cut his cloak in half to share with a beggar on a cold night.

Reverend Francis J. Schikowski, an immigrant from Germany, became the leader of the church in 1890 and served there until his death in 1941. Over the course of his tenure and with the continual growth of the German immigrant population, St. Martin expanded its campus and broadened its services to care for the poor and the needy. In addition to the Becker and Schlacks-designed main Gothic church, a 3-story school was constructed at 5830-38 S. Princeton, designed by Hermann J. Gaul, another noted ecclesiastical architect. There were 30 priests and several thousand attendees at the 1909 dedication of the new school and parish building. A two-year high school was later added and enrollment as well as the number of parishioners continued to increase.

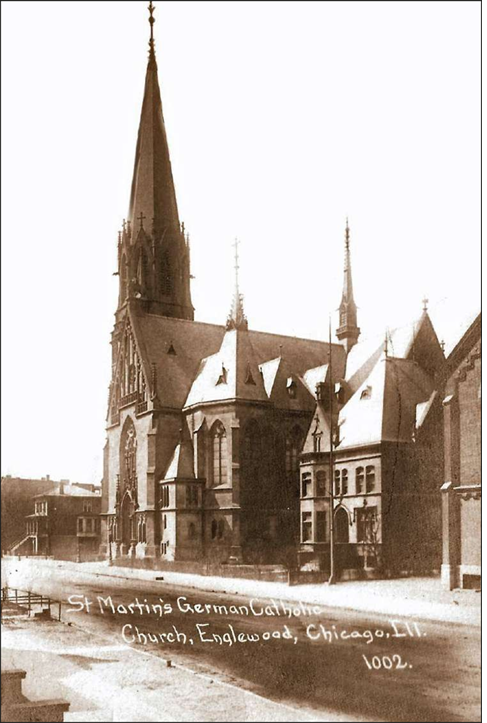

In the 1920s and 1930s, the congregation continued to acquire property and make improvements to the campus. The church was redecorated in 1924, and in 1929 new altars were installed while the organ was rebuilt and enlarged. That same year, additional property north of the school was acquired, and a building at the corner of 59th and Shields Avenue was purchased for use as a convent dormitory. In 1935, the stained glass windows were re-leaded, and the slate on the church tower was replaced. The original statue of St. Martin and the Beggar atop the church’s high gable was also replaced with a new lead-coated copper figure on horseback designed by Gaul, indicating the congregation’s growing prosperity. This statue was even gilded in 1949 and restored again in 1960.Historic view of church and rectory fronting Princeton Avenue. St. Martin de Tours / St. Martin de Porres / Chicago Embassy Church, 1895, Henry J. Schlacks, 5848 S. Princeton Avenue. Photo

Credit: John Chuckman Postcard Collection

By the time of Reverend Schikowski’s death in 1941, the congregation was no longer “thoroughly German,” and English had replaced the German language in sermons, announcements, and parish publications. The postwar era saw Englewood an increasingly multiethnic community. German attendees were joined by Irish, Italian, Lithuanian, Mexican and African American families. At the same time, enrollment at St. Martin’s Catholic School began to fall and non-Catholic students were newly admitted. In the 1950s, the number of African American congregants increased and attendance across both the church and school rose again to levels not seen since the

1920s. By 1961, St. Martin had become a predominantly black parish, with school enrollment 99% African American.

The 1961 construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway displaced many Englewood residents and St. Martin congregants. Although attendance dwindled and financial difficulties persisted, the church remained active in the community, offering a food pantry, senior lunch program, and scouting activities, among other services, until its closure by the archdiocese in 1989. In the decade before its closing, the parish was renamed for St. Martin de Porres, a Black Dominican from Lima, Peru, who comforted the sick and provided for the poor and was canonized in 1962. Even as the church experienced decline, the gilded statue of St. Martin, perched atop the high gable, continued to serve as a familiar landmark for pilots approaching Midway Airport and commuters traveling along the Dan Ryan Expressway.

After its closure, the building stood vacant for almost a decade. When Chicago Embassy Church, an Evangelical Black congregation, purchased the building in 1998, the building was “some sorry stuff.” The congregation’s original leader, Bishop Edward Peecher, and volunteers found the church with no electricity or heat, a floor needing reinforcement, pieces of the ceiling and insulation falling to the floor, and reportedly piles of garbage in place of pews. Chicago Embassy Church took out loans to make necessary repairs, drew 300 attendees from across the city, and eventually began a summer day camp and afterschool program.

In 2006, the massive and iconic gilded statue of St. Martin de Tours was blown off the high gable in a windstorm. It was never repaired or replaced, but as Assistant Bishop Nance of Embassy Church was quoted, “the statue can tell the story of the Englewood community and where it was, and where it is. And our job is to declare where it is going.” Although Chicago Embassy Church stopped operating out of the church building at the corner of Princeton Ave and 59th St. in 2017, and the building has since remained vacant, Preservation Chicago believes that the church can again guide the future of Englewood. With the church restored to its former glory, and its moving and prominent statue replaced, St. Martin’s can again serve as a visual landmark of hope and community on the South Side.

In addition to its role in the history of Englewood’s German and African American community, St. Martin’s magnificent architecture contributes to Chicago’s rich architectural heritage and to the broader canon of Gothic Revival throughout the United States. In 1894, the church was lauded for its purity of gothic detail, including its large Gothic windows with intricate tracery, and crockets decorating a steep gable above its grand main entrances. The church features foliated ornamentation on its main façade, double interlacing tracery above its doorways, blind tracery at the base of its massive corner tower, and narrow arched windows throughout. The church’s integrity to the Gothic form may well derive from its original plans devised by the architect Louis Becker, who sent his drawings to Chicago from Mainz, Germany. The building was realized by Henry J. Schlacks and is considered one of his most impressive built works.

The structure’s most striking feature is its soaring 228-foot-tall steeple atop a massive tower, inset with projecting balconies, pinnacles, and even attached to a turret. The entire building has strong massing and a distinct presence from each angle. The façade is clad in Bedford limestone from Indiana, and its exterior detail is well preserved. Unfortunately, much of the stunning carved wooden interior detail has been lost, but the beautiful stained-glass windows that line the church’s nave and which were designed and manufactured in Munich and Innsbruck studios are still partially extant. The 72-register, 3,000-pipe organ built by Johnson and Son, purchased with funds hard earned by St. Martin’s original congregants, was once played at Chicago’s Central Music Hall, the city’s original Orchestra Hall, and was donated to St. Martin by Mrs. Marshall Field, Jr. The current interior of St. Martin is now quite spare and features mostly plaster and brick in poor condition.

THREAT

St. Martin, despite its deterioration, continues to dominate the built landscape of Englewood’s two-story frame homes. It has acted as a backdrop for the lives of Englewood residents for over 121 years. Unfortunately, its current condition reflects years of deferred maintenance and neglect. Some of its windows have been damaged, the façade has been subject to graffiti, and sections of the roof are in disrepair. Preservation Chicago is worried that the interior is, or will become, exposed to the elements. Without intervention, this grand structure will continue to decline. Its lack of heat, exposure to inclement weather, and deferred maintenance all contribute to worsening conditions. Creative reuse and active occupancy are essential to rehabilitate and preserve the structure.

Recommendations

Despite its condition, St. Martin could surely house a new congregation and continue operating as a place of worship. Assuming lack of interest or demand for continued religious use, the building is nonetheless suited for adaptive reuse. Across Chicago and the United States, numerous former churches and synagogues have been successfully converted to residential, commercial, or even recreational uses.

The structure is orange-rated within the Chicago Historic Resource Survey (CHRS), triggering 90-Day Demolition Delay, and it also easily meets the standards for a Chicago Landmark.

Formal designation as a Chicago Landmark would make a restoration project eligible for City of Chicago Adopt-a-Landmark funding. These funds could help to underwrite the cost of a restoration and ensure that this visual and spiritual landmark of Englewood remains standing and is returned to a productive use.